Up She Rises

Way-hey and up she rises

Way-hey and up she rises

Way-hey and up she rises

Early in the morning

So goes the chorus of the old sea chantey popularized by the Irish Rovers. Those words remind me, as a great many things do, of a morning’s fishing on Nova Scotia’s St. Mary’s River.

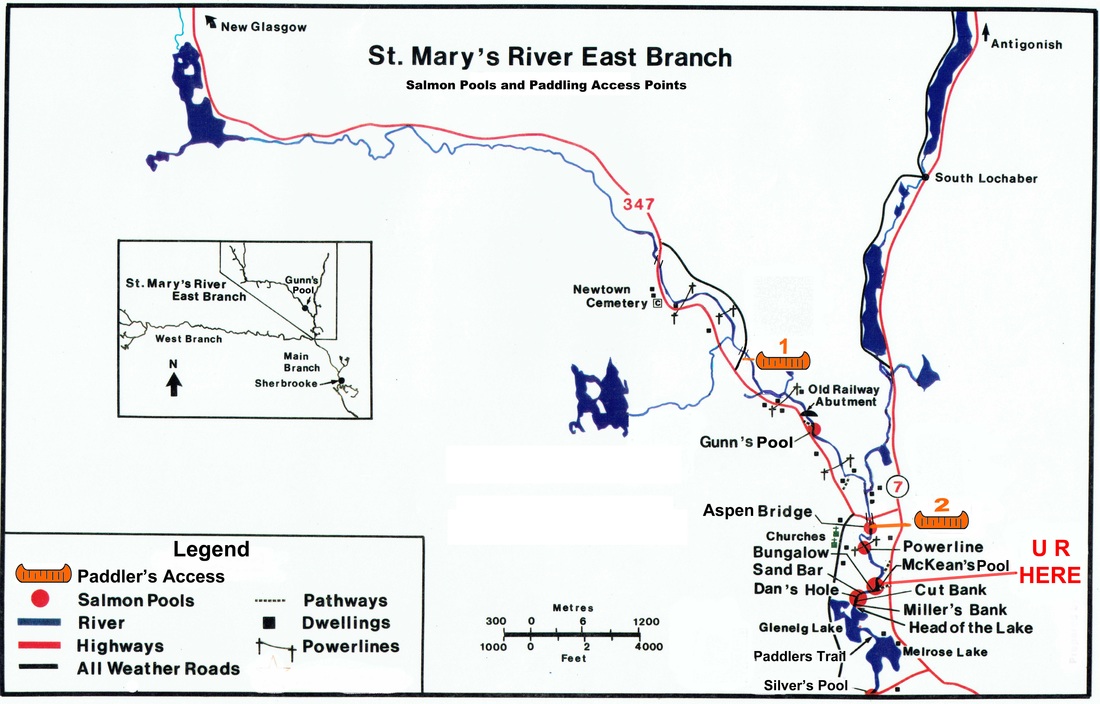

It was mid-June. There were some large salmon in the East Branch but the water level was getting down. This meant the fish would likely be getting fussy and hard to tempt. Fog that blanketed the river was being burned off by the rising sun, the beginning of another wonderful day and St. Mary’s adventure.

I was alone and I had fished a wet fly carefully over MacKeen’s Brook Pool without incident. I switched to a dry fly, one of the popular MacIntosh pattern called the White Hackle Dry. When the fly drifted over the tail of a deep trough a very large salmon rose to it slowly but didn’t touch the fly.

My heart was racing as I prepared for another cast. I knew I should rest the fish for a brief period while I calmed down, so I managed to do so. Feeling ready, I carefully presented the fly again. She rose again without touching it, so I allowed the fly to finish its drift before repeating the cast. This time there was no response so I brought the fly in and paused to consider my situation.

This was clearly the work of a salmon that was in a playful mood rather than an aggressive one. It was an opportunity for a rare experience, a subtle game in which fish and angler play. We weren’t playing for keeps because I released any salmon I caught, but the fish couldn’t know that. In reality, we were on the same team.

Lee Wulff, in his book The Atlantic Salmon, A. S. Barnes & Company, New York, 1958, writes that Jack Young, a Newfoundland guide, said “I don’t believe there’s a more beautiful thing in the world than to see a salmon rise to a dry fly.” To illustrate his strategy for dry fly fishing, Lee describes a hypothetical sequence of fly changes and rests much like the one I was engaged with my St. Mary’s quarry. I remembered Lee’s words from 1958, “The surest way to success with dry fly patterns is to have a variety in size and shape”. Of particular note to today’s dry fly anglers is that Lee did not even mention color as an important factor.

So I switched to another dry fly, this time a medium sized Bomber. Another rise, then nothing. A couple more casts provoked no response, so it was time for another fly change.

I’d been working on this fish for close to 30 minutes and she had risen 3 times. This time a very sparsely dressed and small MacIntosh pattern, the Badger Dry, floated down, bringing a good rise. On the next cast I pulled the fly underwater just over the fish and she rose again, still not touching the fly. Then, nothing.

Another change, this time a big White Wulff, didn’t bring any reaction, so I started to worry. The sun was getting higher and I did not want to end the game this way. So I went back to the White Hackle Dry that located the salmon, and up she rose again, much to my relief. Game’s still on!

The seventh rise also came to the White Hackle Dry. Rises 8 and 9 came to a small Bomber, and the game went on and on until the salmon finally seized a dry fly on the 17th rise.

I struck and she tore out of her lie to the Bungalow Pool just downstream, leaping high and making a spectacular splash when she landed. I followed, there were more runs and a jump, and then the line went slack. She was free!

Not I, however. I was firmly and permanently hooked on the dry fly and the St. Mary’s River. My game wasn’t over and still isn’t!

Here’s one of the dry flies I used in that epic game of long ago, the Pink Lady MacIntosh, an old favourite of mine.

Pink Lady MacIntosh

Hook: #2 – 10 dry fly hook

Thread: Black

Rib: Flat silver tinsel

Body: Pink wool

Wing: Grey squirrel tail

Hackle: 2 light pink cock saddle hackles

Head: Black thread finished with clear head cement

Way-hey and up she rises

Way-hey and up she rises

Way-hey and up she rises

Early in the morning

So goes the chorus of the old sea chantey popularized by the Irish Rovers. Those words remind me, as a great many things do, of a morning’s fishing on Nova Scotia’s St. Mary’s River.

It was mid-June. There were some large salmon in the East Branch but the water level was getting down. This meant the fish would likely be getting fussy and hard to tempt. Fog that blanketed the river was being burned off by the rising sun, the beginning of another wonderful day and St. Mary’s adventure.

I was alone and I had fished a wet fly carefully over MacKeen’s Brook Pool without incident. I switched to a dry fly, one of the popular MacIntosh pattern called the White Hackle Dry. When the fly drifted over the tail of a deep trough a very large salmon rose to it slowly but didn’t touch the fly.

My heart was racing as I prepared for another cast. I knew I should rest the fish for a brief period while I calmed down, so I managed to do so. Feeling ready, I carefully presented the fly again. She rose again without touching it, so I allowed the fly to finish its drift before repeating the cast. This time there was no response so I brought the fly in and paused to consider my situation.

This was clearly the work of a salmon that was in a playful mood rather than an aggressive one. It was an opportunity for a rare experience, a subtle game in which fish and angler play. We weren’t playing for keeps because I released any salmon I caught, but the fish couldn’t know that. In reality, we were on the same team.

Lee Wulff, in his book The Atlantic Salmon, A. S. Barnes & Company, New York, 1958, writes that Jack Young, a Newfoundland guide, said “I don’t believe there’s a more beautiful thing in the world than to see a salmon rise to a dry fly.” To illustrate his strategy for dry fly fishing, Lee describes a hypothetical sequence of fly changes and rests much like the one I was engaged with my St. Mary’s quarry. I remembered Lee’s words from 1958, “The surest way to success with dry fly patterns is to have a variety in size and shape”. Of particular note to today’s dry fly anglers is that Lee did not even mention color as an important factor.

So I switched to another dry fly, this time a medium sized Bomber. Another rise, then nothing. A couple more casts provoked no response, so it was time for another fly change.

I’d been working on this fish for close to 30 minutes and she had risen 3 times. This time a very sparsely dressed and small MacIntosh pattern, the Badger Dry, floated down, bringing a good rise. On the next cast I pulled the fly underwater just over the fish and she rose again, still not touching the fly. Then, nothing.

Another change, this time a big White Wulff, didn’t bring any reaction, so I started to worry. The sun was getting higher and I did not want to end the game this way. So I went back to the White Hackle Dry that located the salmon, and up she rose again, much to my relief. Game’s still on!

The seventh rise also came to the White Hackle Dry. Rises 8 and 9 came to a small Bomber, and the game went on and on until the salmon finally seized a dry fly on the 17th rise.

I struck and she tore out of her lie to the Bungalow Pool just downstream, leaping high and making a spectacular splash when she landed. I followed, there were more runs and a jump, and then the line went slack. She was free!

Not I, however. I was firmly and permanently hooked on the dry fly and the St. Mary’s River. My game wasn’t over and still isn’t!

Here’s one of the dry flies I used in that epic game of long ago, the Pink Lady MacIntosh, an old favourite of mine.

Pink Lady MacIntosh

Hook: #2 – 10 dry fly hook

Thread: Black

Rib: Flat silver tinsel

Body: Pink wool

Wing: Grey squirrel tail

Hackle: 2 light pink cock saddle hackles

Head: Black thread finished with clear head cement

|

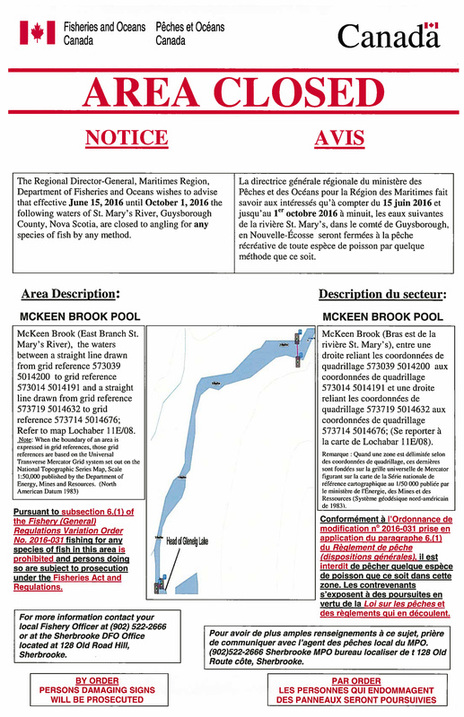

Correction

The fishing closure notice on the right is misleading because it seems to include MacKeen Brook Pool, SMRA's Barrier-Free Access section for disabled fishers. In fact, the closure of this area begins at the Bungalow Pool, immediately below MacKeen Brook Pool, as the riverside signs indicate. |